영화 (1990년)로 잘 알려진 “시라노” 지금까지 프랑스에서 가장 최고 대우 받는 가장 잘 알려진 빅토르 위고 를 뛰어넘어 프랑스 국민에세 가장 최고로 사랑바든ㄴ '시라노' 이라고 한다. 프랑스 혁명 이후 인간 박애의 숭고한 정신을 드높인 불후의 대문호 빅토르 위고 만큼 대단한 위치를 점하는 이 작품은 아마도 인간 에게 떨칠 수 없는 남녀간의 사랑을 두고서 달콤한 문학적 언어의 매력을 내뿜는 '연애' 극이어서 일 것이다. 저작권은 이미 해당되지 않는 고전작품이기에 구텐베르그 e-소설 로 쉽게 찾아 읽을 수 있는 작품인데 인기만큼 실제로 희곡을 읽는지는 모르겠다. 암튼 오늘 구텐베르고 e-book으로 �터 보왔다.

===============

그대 믿음으로 편지를 읽어주오.

이 편지는 내영혼의 육신,

잉크는 사랑으로 상처입은 마음에서 흐르는 피.

그대 향기로운 숨결과 함께 이 글을 읽어주오.

그대의 다정한 음성이 단어들을 어루만질 때,

내 사랑의 상처는 비로소 치유되어질 것이오.

내 손가락들이 흘러간 자리 위에 그대의 키스를 남겨주오.

연약한 미풍과 작은 빗방울들이 나뭇가지를 떨게 하듯,

이 보잘 것 없는 글귀들이 그대의 마음을 움직일 수 있다면

- 시라노 드 벨쥬락 의 편지-

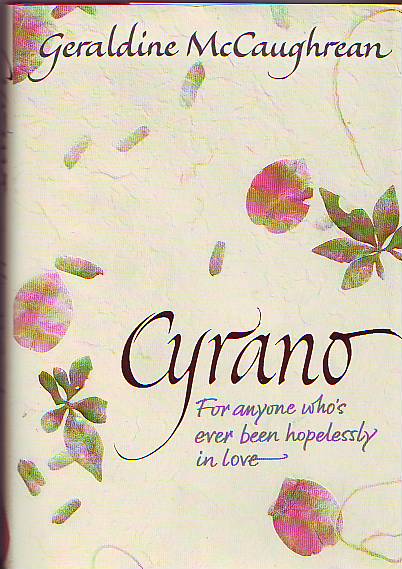

그 때의 감흥을 다시 찾아 보려 ‘시라노’ 소설을 읽었다. 원판 불란서 희곡 작품 (Edmond Rostand) 에서 현대판 소설로 다시 쓴 ‘Cyrano” 을 읽었다. (Geraldine McCaughrean) Oxford University Press 2006년 판.)

다음은 모두 웹 카피한 자료임.

================================

Other versions followed, the latest being Gerard Depardieu in the 1990 version of "Cyrano de Bergerac", but this wasn't nearly the film that Jose Ferrer did. While it might be said that the 1990 Cyrano had more accurate costumes and dialog (with the 1950 version being somewhat on the campy side), Depardieu as Cyrano was somewhat lacking.

(aside: You wouldn't believe how much email I get on this - people seem to really like the Depardieu version!)

Although I initially thought they didn't "enhance" his nose, I've been told they did make it larger. And although I've had several people email me to say that his nose was large enough, I don't feel it was.

As minor as this might seem, the nose of Cyrano was the prime physical characteristic of the play. While Depardieu's nose is on the large side, one can hardly consider it to be the same as the "grotesque protuberance" that Cyrano possessed. Would children run away from Depardieu's nose? I think not!

Despite these drawbacks, after viewing the film again recently, I found myself enjoying the Depardieu version. While I don't think he quite captures the wit that Ferrer does, his passion and delivery of the lines is quite good. The Roxanne in this version is perhaps more true to the original text as well (I'm not sure how many blonds there were in France at that time, as the Ferrer version would suggest!)

"Comic genius Steve Martin delivers an incredible performance as an engaging small town fire chief who has only one tiny flaw - no, make that one HUGE flaw - his astonishingly long nose. Although he considers it no laughing matter, the hilarity never stops as C.D. Bales (Martin) contends with jerky nose jokes, a bumbling crew of firemen, and his secret love for gorgeous astronomy student Roxanne (Daryl Hannah). Unfortunately, she's attracted to fireman Chris (Rick Rossovich), who's tall on looks and short on conversation. And when C.D. agrees to coach the dumbstruck Chris in his pursuit of the fair maiden, this ticklish triangle dissolves into a hilarious series of rib-tickling romantic misadventures. A contemporary love story of mistaken identity and unrequited love, ROXANNE is an unforgettable comedy that Siskel & Ebert & The Movies calls 'A comic masterpiece.' "

Cyrano de Bergerac is a play which exemplifies almost all of the main ideals of romanticism. Three different aspects will be concentrated on in this writing.

First and foremost is the appeal to emotions. All of the other facets of romanticism can be related to the emotional appeal in Cyrano de Bergerac. Because strong emotional appeal is perhaps the most important method used by the author to create identity with the reader, especially in romantic works, the actions which elicit the emotional responses must, then, show a great deal about the character. The character's motives and philosophies can be determined through his actions. Because Cyrano de Bergerac was written in the romantic style, certain intellectual and emotional principles exist throughout the play, which will now be observed in depth.

The overall feeling which one procures after reading Cyrano de Bergerac is a kind of nostalgic sadness. Because the first half of the play is very up-beat, very elated in style, the rather grim ending is that much more bitter.

As the play opens, there is much merrymaking and festivity in preparation for the play. The sheer happiness of all of the colorful characters is transferred to the reader almost instantly. The mood is portrayed very well as being light and bubbly, an overall good feeling. The next major shift comes when Cyrano enters and, after riding himself of Montfleury, puts on the spectacle wherein he demonstrates not only his impeccable verbal dexterity, but also his fencing abilities - and both at the same time. This whole scene causes a strong reaction from the audience, and in turn, the reader. Cyrano is proclaiming his independence and his superiority, but in a way which is neither bragging nor vanity. The reader feels strongly for Cyrano to "go for it!" and is proud and respectful toward him because of his "magnelephant" actions.

Cyrano's actions and the resulting emotional response from the reader, then, portray him as an individual. During this age of romanticism, this was considered to be the "chic" thing to do. Here we have the feeling of the fashionability of Cyrano's actions. He is a moral leader which the people look up to.

As the play progresses, we are shown various incidents in the play which elicit emotional responses from the reader: the longing Cyrano has for Roxane; his belief that he can never have her because of his appearance; a comical intervention as Christian gets a nose up on Cyrano; Cyrano and Christian working together to court Roxane; the author of the letters to Roxane being unknown to her; the passionate speech which Cyrano delivers to Roxane from behind the shrub; the existence of the cadets in such grim conditions; the death of Christian; the final resolution of Cyrano's love for Roxane and his death.

These emotions are what define the play and make it great.

A second characteristic of romanticism is individualism. Throughout the play, it is regarded as noble in spirit to be individualistic, and Cyrano demonstrates to this effect repeatedly. His "white plumes of freedom" are perhaps the most vivid example of this independent spirit. He openly and willingly defies the standards set forth by traditional culture in refusing to dress and act like he is expected to. It is this essence of individualism which gives Cyrano's character such exuberancy, such liveliness, and which makes it fit the romantic movement so perfectly.

The most important thing about the individuality portrayed in this play is the emotional response it evokes. This response, because of the play's romantic nature, was designed as an example of romantic thought and feeling.

Yet another major characteristic of the romantic revolution was intellectual achievement and "deep thought". Unfortunately, there were those who were perhaps a bit lacking upstairs, and they had to settle for only an outward appearance of intellect. They would disguise their intellectual ineptitude by perhaps using big words, or by discussing the same old rhetoric and making it sound a bit nobler than it actually was. In act two, in the pastry shop, after Cyrano has defeated 100 men, there appear on the scene a bunch of would-be poets who are prime examples of this pseudo intellect.

They come in and rub elbows with Cyrano, as if he actually had anything to do with them before he became famous. This pseudo intellect, however distasteful, is indicative of the behavior of the people during the time. In accordance with the ideals of the romantic revolution, the nobility of spirit and individuality must be preserved, and intellect, whether you had it or not, was part of this, because part of being individual was coming up with some of your own ideas, possessing uniqueness of thought. once again, this evokes a certain emotional response from the person who interprets this pseudo intellectualism, and the feeling the reader has about it is an integral part in the establishment of an identity with the characters.

In conclusion, it has been shown that the primary vehicle for the expression of an authors ideas and concepts about a character is the emotional response which is depicted by the characters actions. In romantic works, because of the importance that emotion played in the romantic revolution, the appeal to emotions is the distinct and definitive factor of a good romantic play.

A Collection of Cyrano Essays

Sherri Bray

THE OTHER WAY AROUND

In Act IV when Roxanne arrives at camp with food, there is great celebration. Cyrano is depressed at seeing Christian and Roxanne together and goes for a walk. As Cyrano was trudging through the forest constructing a poem to express his sorrow, he was attacked and killed by the enemy. Word of Cyrano's death traveled quickly back to camp. When Christian heard of the terrible news, he instantly became worried. He didn't know whether to tell Roxanne the truth about Cyrano writing the letters, or just allow her to mourn his death and tell her later. Roxanne sat sobbing in Christian's arms. Then, out of nowhere, Roxanne asked Christian to speak his comforting words to her. At this moment Christian looked teary eyed at Roxanne, and he told her he needed to tell her the truth. Christian proceeded to tell her everything. He told her of the night below her balcony, all of the "forged" letters, and the words Cyrano prepared for him.

When he had finished, he told her he knew she would need time to think and he would leave her alone. He gave her a small hug and walked silently away. As Christian motioned to leave, Roxanne called him back to talk. She told him she cared for him deeply, but her true love died with Cyrano. She said she was extremely sorry, and needed time to mourn Cyrano's death. one year later. .. Roxanne is living in a convent and is told there is a guest waiting in the garden. She arrives in the garden to see Christian waiting nervously. He tells her not to say anything until he's done speaking. He then tells her how much he's sorry for everything, but how much his heart still burns with love for her. He tells her he needed to reveal all of his regrets before he could move on with his life.

He ends by saying he doesn't have the magical, precious words that Cyrano had, but he has a love ever so deep as the one in which Cyrano had shared. Tears rose in Roxanne's eyes as she gave him a hug. She tells him she would never be completely over Cyrano, but there is no one she would rather spend her life with than Christian.

Cyrano De Bergerac: A Wicked Death

From the French News Network:

On the date of September 9, 1655, Cyrano De Bergerac unknowingly and fatally endangered himself by walking under an upstairs window. Little did he know what was going to befall him, quite literally, that crisp autumn morning. We now have a statement from a friend who was near and dear to him.

This statement is from Ragueneau who saw the actual event take place. "It happened like this," Ragueneau starts, "as I was approaching Cyrano's house that afternoon, on my way to visit him, I saw him come out. I hurried to catch up with him. I can't say for certain that it wasn't an accident, but when he was about to turn the corner a lackey dropped a piece of firewood on him from an upstairs window. I rushed to him. My friend was Iying on the ground with a big hole in his head. Then I found a doctor who was willing to come and aid us out of charity.

While the doctor was checking him I went to find Le Bret." "Thank you very much Monsieur Ragueneau. Is there anything else you'd like to add?" asked the reporter. "Yes, I'd like to add that Cyrano's death was very ironic, because he told me one day many years ago the way he wanted to die. He said, 'I hope that when death comes to me it will find me fighting in a good cause and making a clever remark. I want to be struck down by the only noble weapon, the sword, wielded by an adversary worthy of me, and to die not in a sickbed but on the field of glory, with sharp steel in my heart and a flash of wit on my lips.'

"I wouldn't wish on any man to suffer the death that Cyrano suffered. If I knew and could get my hands on the man that killed my friend I would most definitely avenge his death ! " Many of you might've known Cyrano and many might've wished that they hadn't. But Cyrano was a very brave man. Unlike many of us, he was in idealist. He wouldn'tcompromise or change for anyone or anything and that was probably one of the reasons that ultimately led to his death. But he did die, I must say, a very heroic death. They say he was on his feet until the end talking about all of his old enemies and how he wasn't going to give up so easily. We tried to get a statement from Roxane, but she is still in mourning. We will, however, be able to hear her give the eulogy at Cyrano's funeral.

The funeral will be held Sunday morning at 9:00 p.m. De Guiche will also be giving a statement on Cyrano's behalf. Now that we have all heard the story of this brave man's inopportune death I wish that you would all take a moment of silence to remember him whether you were friend or foe. And to Cyrano: may you take your white plume with you always.

Kurtis Gelwicks

Cyrano Alternate Ending

A lonely, pale-green leaf skipped down the street basking in the bright rays of the glaring sun. It was not so bright though, in the local doctor's hospital. It had been about a week after the great war with the Spanish. Many soldiers were having their wounds tended to. The most popular patient seemed to be Christian. Many people crowded around his bed, many giving sympathy to Roxanne. Christian was apparently on his death bed, still in a coma, after being shot. one person not mourning in Christian's room was Cyrano De Bergerac, who was wandering the streets musing over his great dilemma. Should he keep silent and not tell Roxanne anything, or should he honor Christian's wish and reveal the truth to Roxanne? If only Christian would awaken so he could talk with him. Cyrano was walking along with his head down looking at the gravel.

Suddenly, a shadow appeared on the ground, and he jerked his head up to see a log plummeting towards his face. Cyrano's bed now lay beside Christian's. Rageneau had discovered Cyrano's bleeding body and carried it in to the hospital. As both men lay unconscious, everyone's hopes seemed to have diminished. All of a sudden, Roxanne's mournful face turned into a look of shock. Christian's eyes were slowly opening.

"Roxanne...", muttered Christian slowly. "Oh, Christian", rejoiced Roxanne, "you're alive!" "I'm afraid not for long, though", said Christian groggily. "Before I leave you for good, there are some things you must know. It's not me you love Roxanne. The real soul you adore is that of Cyrano De Bergerac's, for he is the one who wrote to you and spoke to you of love. I'm just a fraud." Christian didn't notice Cyrano Iying near him, still unconscious. Roxanne just stared at Christian in awe. Christian continued, his breathing labored,

"But, although Cyrano wrote and talked to you, I loved you just as passionatley!. The only reason I'm still alive is that, although I will never fully have your love, I wanted to be the one to bring you true love!" Just as Christian drew in his last breath, Cyrano's eyes dowly opened, and Roxanne looked eye to eye with the warrior for whom her heart truly yearned.

Mandy Mowen pd3

"she died"

3/11/97

If Roxanne Died...

When Roxanne went to visit Christian at the battlefield, she was unaware of the fact that there were diseases everywhere. She had stayed for quite a while because Christian had been severly wounded. They returned home a few weeks after his remarkable recovery.

Within a year, they had a baby girl and couldn't be happier. Until the day Christian went into Roxanne's room and found her lying in bed, dying. He called for a doctor and while she was being examined, he also called for Cyrano.

"What's the matter, my friend?" Cyrano inqueried.

"It's Roxanne," Christian said. "She's dying. We're not sure from what yet but the doctor sould know soon."

"Roxanne. My only blooming flower in winter and she too will soon parish."

"You must tell her!" Christian exclaimed. "She must leave this world knowing the truth and who it was she really loved and who also loved her."

"No! I can not! She...she must assume they were your words."

After many long minutes of arguing, Christian finally convinced Cyrano to tell Roxanne. They went back into the room to say good-bye.

"Roxanne," Christian said, "Cyrano has something that needs to be told to you."

"What is it?" she asked weakly.

He nudged Cyrano forward. "Go ahead."

"Well," he started, "there is a nagging secret which is pounding in my chest like hail upon a meadow and..."

Just as he was saying this, they heard her whisper,

" I know it was you, the letters, the voice under the balconey. All you. It was you I loved, not Christian. In the begining, yes. That night he was wounded on the battlefield and you were comforting me, I recognized that voice from the balconey and the words from the letters."

She smiled. "I always loved that about you. I loved Christian for his beautiful face and what I thought were his words. But they were yours and I must tell YOU that I. too. love You.l' With that.

"She knew all along! How? Why?" Cyrano exclaimed.

Quietly, Christian said,"We must talk. Outside."

They sat down on a bench and he started. "I must confess this. I was how she knew. I told her everything. It was a day about three weeks ago. We sat right here and talked for a long time. She understood it all. What she told you in there about her loving you was genuine. She really did love you and I told her if this was so I wouldn't stand in her way. But it seems as if a much stronger force did. I'm sure you feel as upset as I but you must remember that she has gone to a far better place and we should grieve for the time needed." With a sigh and a single tear, Christian ended.

"Yes, I will grieve for a long time. But without her, my life no longer has meaning. I will leave now. There is much thinking to be done," Cyrano replied.

That was the last anyone saw Cyrano. No one knows where, or even if, he is living. Those who know this story and were close to Cyrano have made sure that it has lived on as one of the greatest love stories of all time.

Sarah Jacobs

Final Draft

"Roxane finds a good-bye love letter from Cyrano"

To my only love; Roxane, You are my bright shining star and I, your silver moon. Throughout all these years, I have been content with the specks of shimmering stardust, as your light was cast to others. I stood in solitude in the darkness, waiting for a single beam of light. My overwhelming love for you could brighten the entire galaxy, yet was still unseen; unheard. I have chosen this moment, as I am on my deathbed, to explain my absolute and true love. So while I may ascend up to the heavens, my light can still be glowing brightly as I join the eternal sheen of lovers in the sky. Hopefully, my strong glimmer of love shall illuminate your life long after I am gone. There is a difference between me and that of the silver moon; a moon sets daily and is replaced by the rising sun. I shall not set, nor be replaced, but instead, my love will shine constantly. My moonbeams will drench your soul for eternity as I will continue to radiate my undying love. I do have but one request: remember my life, remember my love, and remember me, but not the form in which I left you.

Cyrano De Bergerac

Brandy Searfoss

(~ 3 English

This my friends, is a sorrowful day. The day we must say goodbye to our dear friend Cyrano. There is a terrible melancholy upon us. But now, Cyrano is at a better place. I will now take this time to read a letter that we found on our beloved friend after he passed on. Please join me as we remember our friend, Cyrano.

Dear Loyal Friends,

By this time I am gone to a far better place. I have fallen victim to the worst enemy of all, death. This awful time must come to everyone who is at least mortal, and now my friends, my eternity is beginning. Let your tears not fall; don't weep for me a twinkling longer. Roxane- your eyes, blue and beautiful like the sea- don't let them be darkened by sadness. For now, I drift upon the heavens peering down upon the sea, the land, and my most exquisite friends. I have lived my life to the fullest but now I must rest for all eternity. Love is sculptured in my heart now and forever more. For I shall never forget my one true love, Roxane.

The passion I felt for thee will never be doused by the tears of my eternal rest. My heart seems as though still alive, driven on by the vision of your elegance I captured. There is a special bond that will forever endure in our hearts. My only aspiration was to have our hearts together beat as one. I feel that now, even though I have passed on.

To my friends and Roxane: Love is immortal, unlike human beings, but if we possess this love in our hearts, maybe we too may be immortal. The soul lives on forever on the lips and hearts of those we loved, and those we touched with our presence. To give love, we must also receive it. I have learned multitudinous lessons, I have taken many tests. However, the truest test of all is life, friends, and love.

I, Cyrano de Bergerac, feel as if my life was filled with fortune and ecstasy. With my closing words drawing near, I must say to thee: What comes from thy heart speaks so loudly that sadness cannot be heard, and sorrow not felt. Don't let your tears flow any longer, for life is too short to stand weeping.

Cyrano

What if Christian told Roxane the truth before they left for war?

9~Adrienne Walls pd. 3

[Christian is waking around outside of Roxane's house thinking about the past few days.]

Christian:(to himself) Roxane loves my "soul" not me. She loves Cyrano. I've got to tell her the truth. It is not fair to any of us. (Christian calls for Roxane, she appears and they start to talk.)

Roxane: Oh Christian, my love, what do you wish to speak to me about?

Christian: I haven't been completely honest with you. I'm not the person you love. I didn't write you the letters or poems. I wasn't the one speaking under your balcony that night. The words were not mine. They were Cyrano's. He's the one you love, not me. He has the soul that you love. I don't know how to express my feeling to a woman like he can. I hope you can forgive me. Cyrano and I meant no harm.

Roxane:(looking surprised) What..why...how could you?(with lots of emotions. )

Christian: We wanted to create an "ideal man" for you. To make you happy. Cyrano was the soul and I was the looks. We just wanted the best for you.

Roxane: I don't believe this. You lied to me. I should have known. And that night you only said that you loved me very much, you said it because you didn't have your "soul" with you. I should have guessed. Please go. I need some time to think. (she is very upset and is almost crying.)

[Christian leaves, very upset, to look for Cyrano to tell him what he just told Roxane. He finds Cyrano at the pastry shop.]

Christian: Cyrano, I told Roxane the truth. I couldn't keep Iying to her. I love her too much.

Cyrano:(angrily) You what! You told her the truth without consulting me first. How could you do something so foolish. How am I supposed to face her now? It's ruined. I can never speak to her again.

Christian: You are going to talk to her. She will want to know the whole story, from the both of us.

[Roxane is in room thinkin~ about what Christian had told her. She can't decide if she should go talk to Cyrano or not. Finally she decides to go see him. She finds him at the pastry shop. When Cyrano saw her, he quickly got up to leave but Roxane chased after him.]

Roxane:(calling for Cyrano) Cyrano. I need to know the truth. Please speak to me.[He stops walking away and comes back to her. They sit down to talk.] Was it you who wrote the letters? I know it wasn't Christian. I should have listened to you when you said he was stupid and someone handsome couldn't possibly be smart. I was foolish to have fallen in love with the way he looks but now I love his "soul", and that is your soul. T am in love with you.

Cyrano: No! you don't love me. You love Christian. You could never love someone like me. I don't love you.

Roxane: Yes you do and I love you. Tell me that you love me.

Cyrano: Oh Roxane, I do love you more then anything on this planet.

Roxane: Why didn't you tell me before?

Cyrano: You would have laughed at me. Look at me! I'm not a handsome man like the one you deserve.

Roxane: You are very handsome to me. When I look at you, I don't see your nose, I see your soul, your beautiful soul. That is all that matters to me. I love you.

Cyrano: And I love you.

[Roxane gets a divorce from Christian and then marries Cyrano. Cyrano and the rest ofthe Cadets are sent of~to war by De Guiche. Everyone ofthe Cadets is killed except for Cyrano. He returns after three months on the battle fields. He and Roxane live happily for many years until one day when Cyrano was killed in a duel by one of his many enemies. ]

THE CRITIC

(Thanks to Jean Monroe, we have this wonderful review to read! I found it fascinating...)

It is July of 1898. Max Beerbohm, age 25, has just succeeded George Bernard Shaw as the dramatic critic of London's "Saturday Review." He has been on the job a month when the original Paris production of Rostand's new play "Cyrano de Bergerac" crosses the channel and is mounted (in French) at the Lyceum. Max went to opening night and this is what he thought.

CYRANO DE BERGERAC

July 9, 1898

"The tricolour floats over the Lyceum, and the critics are debating, with such animation as they can muster (at the fag-end of an arduous season) for a play written in a language to which they secretly prefer their own, whether "Cyrano" be a classic. Paris has declared it to be a classic, and, international courtesy apart, July is not the month for iconoclasm. And so the general tendency is to accept "Cyrano" in the spirit in which it has been offered to us. I myself go with that tendency. Even if I could, I would not whisk from the brow of M. Rostand, the talented boy-playwright, the laurels which Paris has so reverently imposed on it.

For even if "Cyrano" be not a classic, it is at least a wonderfully ingenious counterfeit of one, likely to deceive experts far more knowing than I am. M. Rostand is not a great original genius like (for example) M. Maeterlinck. He comes to us with no marvellous revelation, but he is a gifted, adroit artist, who does with freshness and great force things that have been done before; and he is, at least, a monstrous fine fellow. His literary instinct is almost as remarkable as his instinct for the technique-the pyrotechnique-of the theatre, insomuch that I can read "Cyrano" almost as often, with almost as much pleasure, as I could see it played. Personally, I like the Byzantine manner in literature better than any other, and M. Rostand is nothing if not Byzantine: his lines are loaded and encrusted with elaborate phrases and curious conceits, which are most fascinating to any one who, like me, cares for such things.

Yet, strange as it seems, none of these lines is amiss in the theatre. All the speeches blow in gusts of rhetoric straight over the footlights into the very lungs of the audience. Indeed , there is this unusual feature in M. Rostand's talent, that he combines with all the verbal preciosity of extreme youth the romantic ardour and technical accomplishment of middle-age. Hence the comparative coldness with which he is regarded in Paris by lesjeunes, who naturally do not like to scratch Mallarme and find Sardou.

Not the debased Sardou himself has the dramaturgic touch more absolutely than has M. Rostand. But M. Rostand is not, like M. Sardou, a mere set of fingers with the theatre at the tips of them. on the contrary, he is a brain and a heart and all sorts of good things which atone for-or, rather, justify-the fact that "Cyrano" is of the stage stagey. It is rather silly to chide M. Rostand for creating a character and situations which are unreal if one examine them from a non-romantic standpoint. It is silly to insist, as one or two critics have insisted, that Cyrano was a fool and a blackguard, in that he entrapped the lady of his heart into marriage with a vapid impostor. The important and obvious point is that Cyrano, as created by M. Rostand, is a splendid hero of romance.

If you have any sensibility to romance, you admire him so immensely as to be sure that whatever he may have done was for the best. All the characters and all the incidents in the play have been devised for the glorification of Cyrano, and are but, as who should say, so many rays of lime-light converging upon him alone. And that is as it should be. The romantic play which survives the pressure of time is always that which contains some one central figure, to which everything is subordinate-a one-part play, in other words. The part of Cyrano is one which, unless I am much mistaken, the great French actor in every future generation will desire to play. Cyrano will soon crop up in opera and in ballet.

Cyrano is, in fact, as inevitably a fixture in romance as Don Quixote or Don Juan, Punch or Pierrot. Like them, he will never be out of date.

But prophecy is dangerous? Of course it is. That is the whole secret of its fascination. Besides, I have a certain amount of reason in prophesying on this point. Realistic figures perish necessarily with the generation in which they were created, and their place is taken by figures typical of the generation which supervenes. But romantic figures belong to no period, and time does not dissolve them. Already Ibsen is rather out of date-even Mr. Archer has washed his hands of Ibsen-while the elder Dumas is still thoroughly in touch with the times.

Cyrano will survive because he is practically a new type in drama. I know that the motives of self-sacrifice-in-love and of beauty-adored-by- a-grotesque are as old, and as effective, as the hills, and have been used in literature again and again. I know that self-sacrifice is the motive of most successful plays. But, so far as I know, beauty-adored-by- a-grotesque has never been used with the grotesque as stage-hero. At any rate it has never been used to finely and so tenderly as by M. Rostand, whose hideous swashbuckler with the heart of gold and the talent for improvising witty or beautiful verses-Caliban + Tartarin + Sir Galahad + Theodore Hook was the amazing recipe for his concoction-is far too novel, I think, and too convincing, and too attractive, not to be permanent.

Whether, in the meantime, Cyrano's soul has, as M. Rostand gracefully declares, passed into "vous, Coquelin," I am not quite sure. I should say that some of it-the comic, which is, perhaps the greater part of it-has done so. But I am afraid that the tragic part is still floating somewhere, unembodied. Perhaps the two parts will never be embodied together in the same actor.

Certainly, the comic part will never have a better billet than its first.

"I have said that the play is unlikely to suffer under the lapse of time. But though it has no special place in time, in space it has its own special place. It is a work charged with its author's nationality, and only the compatriots of its author can to the full appreciate it. Much of its subtlety and beauty must necessarily be lost upon us others. To translate it into English were a terrible imposition to set any one, and not even the worst offender in literature deserves such a punishment. To adapt it were harder than all the seven labours of Hercules rolled into one, and would tax the guile and strength of even Mr. Louis Parker.

The characters in the "Chemineau" had no particular racial characteristics, and their transportation to Dorsetshire did them no harm. But there is no part of England which corresponds at all to the Midi. An adapter of Cyrano" might lay the scene in Cornwall, call the play "Then Shall Cyrano Die?" and write in a sixth act with a chorus of fifty thousand Cornishmen bent on knowing the reason why, or he might lay it in any of the other characteristic counties of England, but I should not like to answer for the consequences. However, the play will of course be translated as it stands. And, meanwhile, no one should neglect this opportunity of seeing the original production. There is so much action in the piece, and the plot itself is so simple, and even those who know no French at all can enjoy it.

And the whole setting of the piece is most delightful. I was surprised on the first night to see how excellent was the stage management. Except a pair of restive and absurd horses, there was no hitch, despite the difference of the Lyceum and the Porte Saint Martin. Why, by the way, are real horses allowed on the stage, where their hoofs fall with a series of dull thuds which entirely destroy illusion? Cardboard horses would be far less of a nuisance and far more convincing. However, that is a detail. I wish all my readers to see "Cyrano." It may not be the masterpiece I think it, but at any rate it is one's money's-worth. The stalls are fifteen shillings a-piece, but there are five acts, and all the five are fairly long, and each of them is well worth three shillings. Even if one does not like the play, it will be something, hereafter, to be able to bore one's grandchildren by telling them about Coquelin as Cyrano."

Less than two years later, Max's prediction is fulfilled and an English translation of the play goes up in London. As he also predicted, he didn't like it.

"CYRANO" IN ENGLISH

April 28, 1900

one evening, some years ago, I had been dining with a friend who was supposed to have certain spiritualistic powers. As we were very much bored with each other, I proposed that we should have a seance. Though doubtful whether I should be "sympathetic," he was quite willing to try.

The question arose, with what spirit should we commune. He suggested Madame Blavatsky. I was all for Napoleon Buonaparte. Finally-by what process I forget-we agreed on Charlotte Corday. The lights having been turned out, we sat down at a small table. Placing the tips of our fingers on it, we thought of Charlotte Corday with all our might. Many minutes went slowly by, and the table showed no signs of animation. My friend said it was very strange. After a fruitless hour or so, he seemed to be so much annoyed that I thought it would be only kind to press my fingers in such a way as to make the table tilt duly towards me for a moment and then tilt back. I did this. "Are you there?" asked my friend, in a low voice. I pressed again, producing the requisite number of taps for "yes." "Who are you?" my friend rejoined. "Charlotte" I rapped out.

I continued to rap appropriate answers to my friend until I thought he had had enough enjoyment for one evening. The spirit having evidently withdrawn to its own sphere, he turned up the lights, pronounced the seance a great success, and told me that I seemed to have some power as a medium. But I have never taken the advice he gave me to develop this power, and I recall our evening merely because I was irresistibly reminded of it, the other night, when I saw the English version of "Cyrano" at Wyndham's Theatre. I saw, with my mind's eye, the manner in which the whole play was written.

There were Mr. Stuart Ogilvie and Mr. Louis N. Parker, seated solemnly on either side of a small table, trying to raise the spirit of Cyrano. "It is very strange," said Mr. Ogilvie, frowning; "the table does not seem to move." Genial Mr. Parker, hating that his friend should be disappointed, brought illicit pressure to bear on the table. "Are you there?" asked the author of "Hypatia," in a broken whisper. "Yes," rapped Mr. Parker, smiling inwardly. And so the mockery was inaugurated. So the collaboration went forward, hollow rap by rap, laboriously, portentously, with no more real evocation than was got in the seance I have described.

"Alas, that any pretence of raising this ghost need have been made among us! When first M. Coquelin brought M. Rostand's play to England I expressed a pious hope that it would not be translated. Of course, I knew well that it would be. Cyrano, the man, got safely home from the Hotel de Bourgogne, routing with his own sword the hundred rascals who lay in wait for him; but Cyrano, the play, would not escape its English obsessors so easily. It might slip through the fingers of one and another of the hundred desperate actors who were thirsting to produce it. It might keep the whole gang at bay for a while. But in the end it would, inevitably, be taken. And, of course, it could only be taken dead: the nature of things prevented it from being taken alive. I dare say that I explained that fact at the time. But of what use was it to argue against a foregone conclusion? Cyrano, in the original version, is the showiest part of modern times-of any times, maybe.

Innumerable limelights, all marvellously brilliant, converge on him, And as he moves he flashes their obsequious radiance into the uttermost corners of the theatre. The very footlights, as he passes them, burn with a pale, embarrassed flame, useless to him as stars to the sun. The English critic, not less than the English actor, is dazzled by him. But, though he shut his eyes, his brain still works, and he knows well that an English version of Cyrano would be absurd. Cyrano, as a man, belongs to a particular province of France, and none but a Frenchman can really appreciate him.

An Englishman can accept the Gascon, take him for granted, in a French version, but not otherwise. Cyrano is a local type; not, like Quixote or Juan, a type of abstract humanity which can pass unscathed through the world. Nor is he, like Quixote or Juan, a possible individual, such as one might meet. Even in Gascony he were impossible. He is the fantastically idealised creation of a poet. In M. Rostand's poetry, under the conditions which that poetry evokes, he is a real and solid figure, certainly. But put him into French prose, and what would remain of him but a sorry, disjointed puppet? Put him into English prose (or into the nearest English equivalent that could be found for M. Rostand's verse) and-but the result, though it can be seen at Wyndham's Theatre, cannot be described. All of this I foresaw, being a critic. But the actors, not they. Creatures of impulse, they saw nothing but the chance of playing Cyrano. Mr. Wyndham happens to be the man who ultimately got it. But as the part does not, from a critic's standpoint, exist, how am I to praise his performance of it? how, as one who revels in his acting, do aught but look devoutly forward to his next production?"

Source: Beerbohm, Max. Around Theaters (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1953), pp. 4-7, 73-75.

He ends by saying he doesn't have the magical, precious words that Cyrano had, but he has a love ever so deep as the one in which Cyrano had shared. Tears rose in Roxanne's eyes as she gave him a hug. She tells him she would never be completely over Cyrano, but there is no one she would rather spend her life with than Christian.

While the doctor was checking him I went to find Le Bret." "Thank you very much Monsieur Ragueneau. Is there anything else you'd like to add?" asked the reporter. "Yes, I'd like to add that Cyrano's death was very ironic, because he told me one day many years ago the way he wanted to die. He said, 'I hope that when death comes to me it will find me fighting in a good cause and making a clever remark. I want to be struck down by the only noble weapon, the sword, wielded by an adversary worthy of me, and to die not in a sickbed but on the field of glory, with sharp steel in my heart and a flash of wit on my lips.'

'문·사·철+북 리딩 > 책 읽기의 즐거움' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Thoreau (0) | 2008.07.11 |

|---|---|

| <명상록> (0) | 2008.04.29 |

| 인간의 <집단 지능> (0) | 2007.12.20 |

| ‘생산으로서의 욕망’ <안티오이디푸스> (0) | 2007.12.15 |

| Basic Instincts (0) | 2007.10.09 |